“Recently, Mycobacterium lepromatosis, a new unculturable mycobacterial species associated with diffuse lepromatous leprosy, also known as Lucio’s leprosy or Latapi’s leprosy, was described by Han et al.” (Singh and Cole 2011)

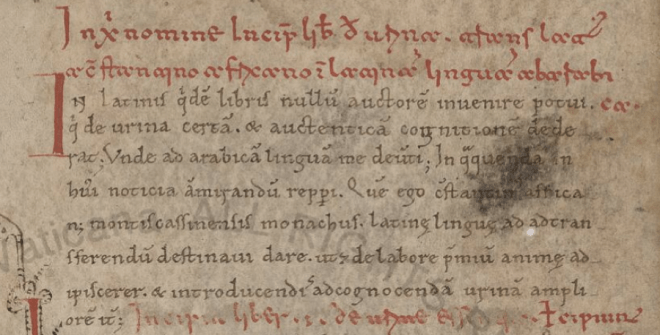

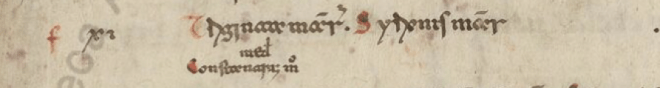

Housed high at the monastery of Monte Cassino in southern Italy, looking out over the Mediterranean world, what would Constantinus Africanus, our leprosy specialist from 1000 years ago, have made of this news of a “new” species of leprosy? As the author of the earliest specialized Latin treatise on leprosy, he would have understood that the disease manifested in different ways. As the translator of works that would shape the face of European medicine for the next 400 years, he would have understood the incredible capacity of medical knowledge to alleviate human suffering.

The modern abbey of Monte Cassino. Source: Martin Collin, Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:View_of_Monte_Cassino_monastery_from_Polish_cemetery.jpg, accessed 25.i.2026.

But there was also much he wouldn’t have been able to process. He would have had no mental framework to grasp the concept of “bacteria.” Not simply would the Mexican physicians Rafael Lucio Nájera (1818-1866) and Fernando Latapí (1902-1989) have been unknown to him, but so would the very idea of “Mexico.”1 He would have had trouble seeing how both this “second species” of leprosy as well as the first (Mycobacterium leprae, discovered in 1873) could be connected to human migrations over the course of millennia, for he would have had no concept of evolution.

Nevertheless, he may be just the inspiration we need right now. This year, as we celebrate World Leprosy Day 2026, the modern world’s infrastructure of global health is being torn apart as the result of anti-science and anti-immigrant sentiments. This 11th-century Arabic-speaking North African émigré/Italian immigrant, who first introduced Islamic medicine to Christian Europe, is not only a representative of science, but also a reminder of the role migration plays in human health and disease. It is part of who we are as humans, and it has been because of human migrations that many infectious diseases have been acquired. And it has also been in the process of fighting infectious diseases that the medical arts and sciences have been born.

Confirming the Deep Human History of Mycobacterium lepromatosis in the Americas

In this past year, one of the youngest fields of science, paleogenomics, pushed back the history of leprosy in the “new” worlds of the Americas by at least 10,000 years. As specialists in leprosy around the world will admit, social stigma creates barriers to open discussion and humane treatment. Although leprosy has long carried that burden, recognizing it as a global disease gives us a new way to think beyond stigma and focus instead on shared histories.

In 2023, I wrote about both Han’s leprosy, M. lepromatosis, and Hansen’s disease, M. leprae. When I first learned about M. lepromatosis in 2012, four years after it had been clinically described in 2008 by its real discoverer, Xiang-Yang Han (an infectious disease specialist at the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston), my immediate thought was “How can there be a ‘new’ species of such an old, slowly evolving disease?” I followed Han’s subsequent work

on the genetic structure and epidemiology of M. lepromatosis and saw that he, too, suspected that the organism had a very deep history. So deep, in fact, it must have predated modern humans.

That gut sense was confirmed this past year, when two separate studies retrieved molecular fragments of the organism from buried remains in the Americas dating back, in one case, to at least 4000 years ago (Ramirez et al. 2025). Even that estimate was likely conservative, since the evolutionary distance between the strains recovered from Canadian and Argentinian aDNA and a living strain still found in North America suggested that the organism may have been circulating in human hosts for at least 10,000 years (Lopopolo et al. 2025). Comparing the evolution of the two leprosies (which are more closely related to each other than any other known organisms in the world), it now seems that, evolutionarily, they may have diverged from each other somewhere between 700,000 and 2 million years ago.

Since modern humans did not exist 700,000 years ago, in what host(s) have these two diseases persisted? It was already well known that at least one of the Old World strains of leprosy, M. leprae, established itself among armadillos in the Americas following its importation into the Americas, perhaps as early as the 16th century. But that was clearly a new, post-Contact transference from humans to armadillos. As discussed in the World Leprosy Day blogpost last year, squirrels have now been confirmed in the transmission of leprosy in medieval England, no doubt thanks to the intense use of squirrel furs for a high-end cloak lining known as vair. But whether humans gave it to squirrels, or squirrels to humans, is still unclear.

The squirrel connection was all the more perplexing because it has been known since 2014 that M. lepromatosis (the “American” leprosy) also is found in squirrels in the United Kingdom. It is now estimated that the lineage of M. lepromatosis found in UK squirrels branched off from its known American cousins about 3000 years ago. When (and how) it was transferred eastward across the Atlantic remains completely unclear.

Infectious Diseases, Migration Histories, and Candlesticks

Even beyond the squirrel question, having the history of leprosy in the Americas so vastly expanded by just two studies allows us to situate this “new world” disease against our narratives of its closest known “old world” relative, M. leprae, whose pre- and post-Contact globalizing histories have been recounted in previous posts. For the post-Contact history, family trees of M. leprae’s modern genomes have informed us about its westward transmission across the Atlantic as systems of colonization and slavery expanded (Green 2022). For the pre-Contact period, we already know the evolutionarily oldest strains are found near the Pacific Rim coast, with expansion eastward into the Pacific Islands (Green 2025a) hundreds of years before Europeans and Africans regularly crossed the Atlantic.

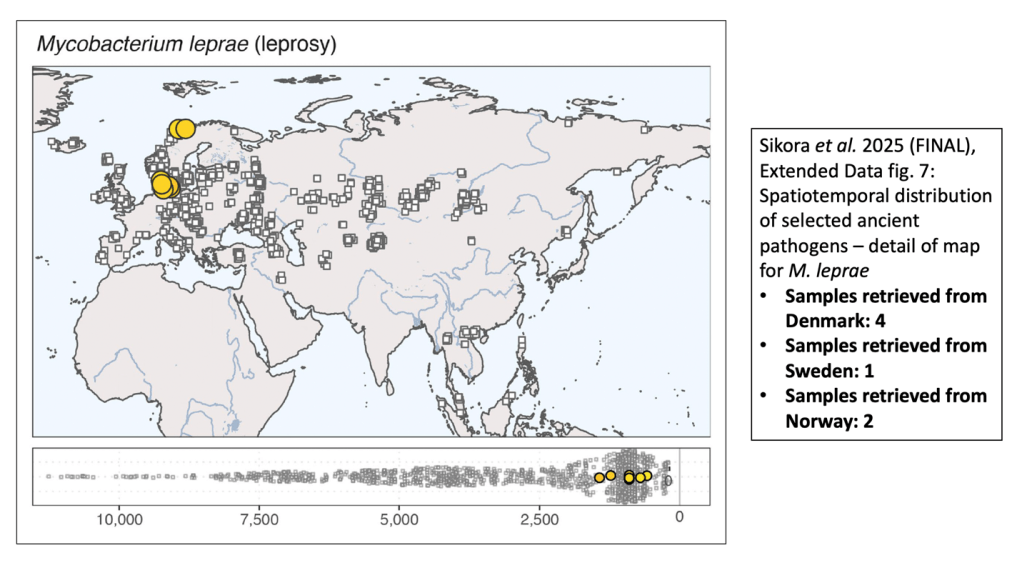

For more than a decade, molecular clock estimates have suggested that M. leprae’s sustained history in humans only went back about 5-6000 years. Interestingly, a major study published this past year looking at a variety of infectious diseases in humans across Eurasia for the past 37,000 years found a similar pattern:

“Zoonotic pathogens are only detected from around 6,500 years ago, peaking roughly 5,000 years ago,coinciding with the widespread domestication of livestock. Our findings provide direct evidence that this lifestyle change resulted in an increased infectious disease burden. They also indicate that the spread of these pathogens increased substantially during subsequent millennia, coinciding with the pastoralist migrations from the Eurasian Steppe.” (Sikora et al. 2025)

A cumulative map of M. leprae aDNA retrieved thus far from Afro-Eurasia is actually much fuller than this, but it is painting a fairly consistent picture. Most of that expansion seems to have happened in the past 2500 years or so. Circumstantially, many of those expansions seem to have been within the context of human migrations, either voluntary or involuntary.

Just this past week, a team of bioarchaeologists and paleogeneticists published another aDNA study documenting the presence in Colombia at least 5000 years ago of a strain of another human pathogen, Treponema pallidum, that was a “sister” to the strains that would branch into the three subspecies we know today causing syphilis (T. p. pallidum), yaws (T. p. pertenue), and bejel (T. p. endemicum). Noting that such discoveries “make it possible to move beyond simplistic ideas of where diseases geographically come from,” an editorial accompanying the study observed that:

“Far from static or specific to a human population or environment, pathogens are tethered to mobile human and animal hosts and reservoirs, molded by human experiences and biosocial and environmental conditions, adaptable, and globalized.” (Zuckerman and Bailey 2026)

Like leprosy, syphilis has been a disease that, at least once it manifested in Europe at the end of the 15th century, elicited stigma and ostracization. But to say that hatred or bigotry are perennial companions of infectious disease shows an unawareness of history. Reactions have never been uniform. Bioarchaeology repeatedly gives us examples of care rather than ostracism; the historical record is increasingly giving us evidence of communalism in the face of overwhelming pandemic onslaughts, not just anarchy and accusations (Green 2025b).

As paleogenomics offers us, for the first time, the opportunity to construct long evolutionary histories of the world’s most impactful diseases, we have the opportunity to rethink what it means for pathogens to be “tethered” to our histories. Combining those material histories of disease with intellectual and social histories of the medical arts and sciences allows us to reconceive how science itself is part of the landscape we have created. Note that word “adaptable.” Just as the pathogens adapt to new hosts (human and animal), so medical science has allowed humans to continually adapt to new environments. And medical science is necessarily cumulative. There is a reason the first Hippocratic aphorism reads “Life is short. The art is long.”

In the United States, where I write today, science and immigrants are both under attack. The entire system of public health infrastructures—from vaccines to food safety to environmental protections—is being dismantled at the same time that extraordinarily cruel measures are being implemented to chase out and deport immigrants exactly like Constantine would have been a millennium ago.

Once again, Constantine helps reset our balance. A 12th-century pair of exquisitely crafted candlesticks, perhaps made at the Belgium abbey of Stavelot, depict the world’s three (!) continents and what each offered human culture (Qassiti 2026, drawing on Müller 2023). AFRICA displays an open book with the inscription SCIENTIA—wisdom, learning, science. MEDICINA and THEORICA/PRACTICA (theory and practice), on the other candlestick, seem to be a particular nod to Constantine’s recent impact on medical learning in Europe. Is it a coincidence that the abbot of Stavelot, Wibald (1098-1158), had himself briefly served as abbot of Monte Cassino around the time these extraordinarily crafted works of art were made?

Details of the Hildesheim candlesticks with allegorical figures associating Scientia with Africa (left), and Theorica and Practica (right) with Medicina, 12th century. Source: Fotograf*in: Christian Tepper; https://www.bildindex.de/document/obj20313186, accessed 25.i.2026.

Infectious diseases arise because humans do what humans do. They interact with their environments. They explore. They migrate. The medical sciences and humanities are our response to the accidental harms we encounter. Leprosy’s long global history reflects back at us the millennia of encounters we’ve had with this disease. Its mirror also shows us the choices we can make now in living up to our fullest potential as human beings: to care for each other, celebrating the wisdom we have acquired and seeking even more. May we all be candles of such light!

This essay is dedicated to the memory of Francis Lanneau Newton, (28 February 1928 – 14 February 2025), amicus optimus Constantini Africani.

Further Reading:

Bozzi, Davide, Nasreen Z. Broomandkhoshbacht, Miguel Delgado, Jane E. Buikstra, Carlos Eduardo G. Amorim, Kalina Kassadjikova, Melissa Pratt Estrada, Gilbert Greub, Nicolas Rascovan, David Šmajs, Lars Fehren-Schmitz, Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas, and Elizabeth A. Nelson. “A 5500-year-old Treponema pallidum Genome from Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia,” Science 391, no. 6783 (22 Jan 2026).

Gili, Anna. Leprosy in the Mediterranean Medical Literature: The ‘Kitāb al-Malakī’ and Related Texts (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2026).

Green, Monica H. “Leprosy as an Endemic Disease: The US and Brazil,” Twitter thread for World Leprosy Day 2022, 30 January 2022, archival copy posted on Knowledge Commons, https://doi.org/10.17613/fn8m2-xwp73.

Green, Monica H. “Hansen’s Disease, Han’s Disease, and the Global History of Leprosy – World Leprosy Day 2023 Twitter thread,” Twitter, 29 February 2023, archived at Knowledge Commons, https://doi.org/10.17613/padf2-vcj87.

Green, Monica H. “The Stigma of Neglect: Why We Know Less Than We Should About Medieval Leprosy. A Post in Honor of World Leprosy Day 2024,” Constantinus Africanus (blog), 28 Jan 2024, https://constantinusafricanus.com/2024/01/28/the-stigma-of-neglect-why-we-know-less-than-we-should-about-medieval-leprosy/, archived at Knowledge Commons, https://doi.org/10.17613/f2sv4-73114 .

Green, Monica H. “Leprosy in the Global Middle Ages: A Slow Pandemic. A Post in Honor of World Leprosy Day 2025,”

Constantinus Africanus, 26 Jan 2025, https://constantinusafricanus.com/2025/01/26/leprosy-in-the-global-middle-ages-a-slow-pandemic/, archived copy on Knowledge Commons, https://doi.org/10.17613/y59xw-v4g32. [Green 2025a]

Green, Monica H. The Black Death: The Medieval Plague Pandemic Through the Eyes of Ibn Battuta, History for the 21st Century (H21) Project, 01 Sep 2025, https://www.history21.com/owit-module/the-black-death-the-medieval-plague-pandemic/, https://doi.org/10.17613/qeznz-tcx61. [Green 2025b]

Lopopolo, Maria, Charlotte Avanzi, Sebastian Duchene, Pierre Luisi, Alida de Flamingh, Gabriel Yaxal Ponce-Soto, Gaetan Tressieres, Sarah Neumeyer, Frédéric Lemoine, Elizabeth A. Nelson, Miren Iraeta-Orbegozo, Jerome S. Cybulski, Joycelynn Mitchell, Vilma T. Marks, Linda B. Adams, John Lindo, Michael DeGiorgio, Nery Ortiz, Carlos Wiens, Juri Hiebert, Alexandro Bonifaz, Griselda Montes de Oca, Vanessa Paredes-Solis, Carlos Franco-Paredes, Lucio Vera-Cabrera, José G. Pereira Brunelli, Mary Jackson, John S. Spencer, Claudio G. Salgado, Xiang-Yang Han, Camron M. Pearce, Alaine K. Warren, Patricia S. Rosa, Amanda J. de Finardi, Andréa de F. F. Belone, Cynthia Ferreira, Philip N. Suffys, Amanda N. Brum Fontes, Sidra E. G. Vasconcellos, Roxane Schaub, Pierre Couppié, Kinan Drak Alsibai, Rigoberto Hernández-Castro, Mayra Silva Miranda, Iris Estrada-Garcia, Fermin Jurado-Santacruz, Ludovic Orlando, Hannes Schroeder, Lluis Quintana-Murci, Mariano Del Papa, Ramanuj Lahiri, Ripan S. Malhi, Simon Rasmussen, and Nicolás Rascovan. “Uncovering Pre-European Contact Leprosy in the Americas and Its Enduring Persistence,” Science 389 (24 Jul 2025), eadu7144.

Müller, Kathrin. “Sancta Sapientia and the Science of Medicine: A Pair of Twelfth-Century Candlesticks with Female Allegories in Hildesheim,” Codex Aquilarensis 39 (2023), 61–78.

Qassiti, Mohamed. “Constantinus Africanus – A North African Migrant Revolutionises Medieval Latin Medicine,” Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek, 13 Jan 2026, https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/content/blog/constantinus-africanus-ein-nordafrikanischer-migrant-revolutioniert-die-lateinische-medizin-des-mittelalters?lang=en.

Ramirez, Darío A., T. Lesley Sitter, Sanni Översti, María José Herrera-Soto, Nicolás Pastor, Oscar Eduardo Fontana-Silva, Casey L. Kirkpatrick, José Castelleti-Dellepiane, Rodrigo Nores and Kirsten I. Bos. “4,000-Year-Old Mycobacterium lepromatosis Genomes from Chile Reveal Long Establishment of Hansen’s Disease in the Americas,” Nature Ecology and Evolution 9 (2025), 1685–1693.

Sikora, Martin, Elisabetta Canteri, Antonio Fernandez-Guerra, Nikolay Oskolkov, Rasmus Ågren, Lena Hansson, Evan K. Irving-Pease, Barbara Mühlemann, Sofie Holtsmark Nielsen, Gabriele Scorrano, Morten E. Allentoft, Frederik Valeur Seersholm, Hannes Schroeder, Charleen Gaunitz, Jesper Stenderup, Lasse Vinner, Terry C. Jones, Björn Nystedt, Karl-Göran Sjögren, Julian Parkhill, Lars Fugger, Fernando Racimo, Kristian Kristiansen, Astrid K. N. Iversen, and Eske Willerslev. “The Spatio-temporal Distribution of Human Pathogens in Ancient Eurasia,” Nature 642 (24 Jul 2025), 1011-1019.

Singh, Pushpendra, and Stewart T. Cole. “Mycobacterium Leprae: Genes, Pseudogenes and Genetic Diversity,” Future Microbiology 6, no. 1 (2011), 57–71, https://doi.org/10.2217/fmb.10.153.

Zuckerman, Molly K. and Lydia Bailey. “Uncovering the Secrets of Syphilis,” Science 22 January 2026, 352-353, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aee7963.

1 Constantine had, of course, had close associations with the Norman nobility who arrived in southern Italy around the same time he did (and who may have even commissioned his treatise on leprosy). Whether anyone in these circles knew about the possible Norse encounters with Mesoamerica around the year 1000 is unclear; see Valeria Hansen, The Year 1000: When Explorers Connected the World—and Globalization Began (New York: Scribner, 2020).